The purpose of this article is to give a basic understanding of what a patent is, what types of patents there are, what the various parts of a patent consist of, and how the claims of a patent are to be interpreted. There is a difference between a patent’s legal analysis and it’s technical analysis. Although this article may highlight some of the legal analysis from a very high level, GHB Intellect provides technology- and business-focused consultancy and does not offer accounting, tax, investment or legal advice, analysis, or representation.

Excerpt:

What is a patent? Patents grant the property rights to an invention. In the U.S., patent applications are submitted to the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) for a 20 year term. There are three types of patents, namely, design, utility, and plant patents. The claims are the heart of a patent; they define the limits of exactly what the patent does and does not cover. The below pdf is a sample of an approved patent.

What is a Patent

When an inventor files for a patent, s/he is requesting a grant of a property right to an invention. This right is granted by the appropriate governmental agency having jurisdiction in the region of the world where the inventor is filing. For example, in the US, the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) issues such grants for a term of 20 years from the date of the application. As such, a granted patent is only valid for the duration of the term of the patent and only in the region of the world where the patent office has jurisdiction.

The right conferred by the patent grant is “the right to exclude others from making, using, offering for sale, selling, or importing” the invention. Note, a patent does not give the right to make, use, offer for sale, sell or import, only the right to exclude others.

A common mistake is to confuse patents with trademarks and copyrights. A trademark is a right to prevent others from using a word, name, symbol, or device to distinguish the source of the goods in trade. This is not a right to prevent others from making, using, offering for sale, selling, or importing those goods.

Copyright is a right given for protection of “original works of authorship,” published or otherwise. The distinction to be made here relative to patents is that copyrights protect the form of expression not the subject matter. For example, a user manual for a machine may be copyrighted, but this only protects the owner of the copyright from others copying and reproducing the content of the manual. However, the copyright does not prevent others from publishing a different description of the machine or from making/selling/importing the machine itself.

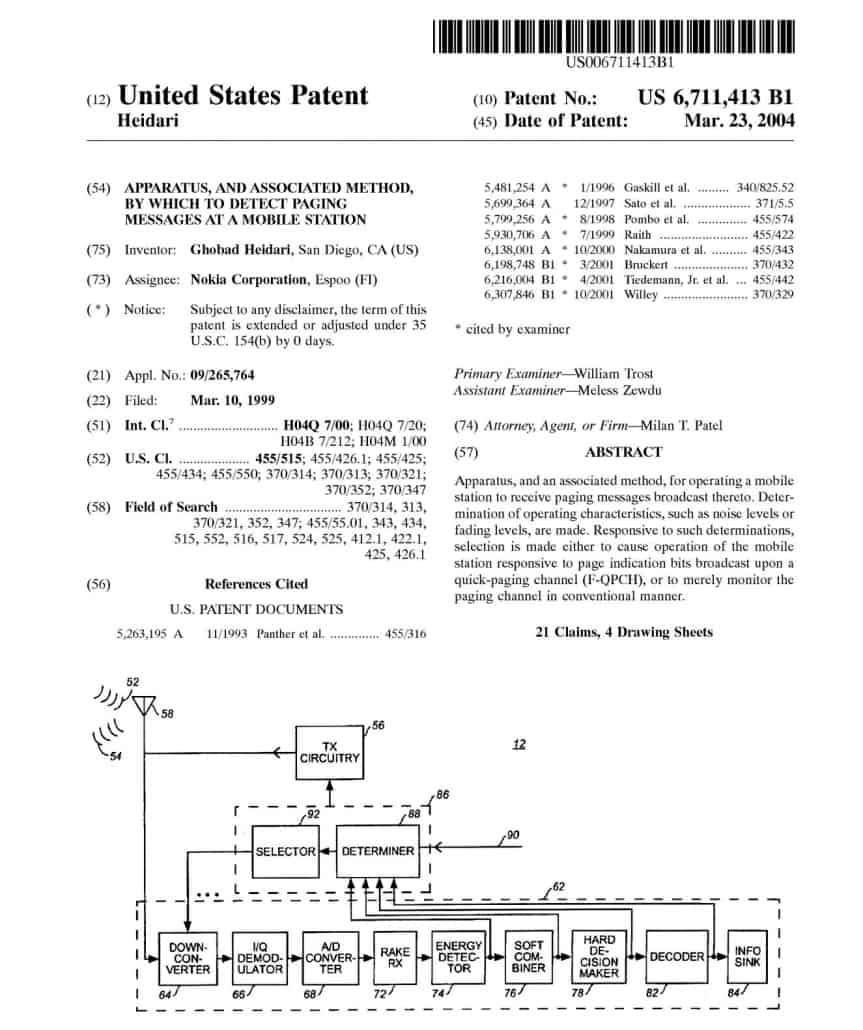

Below is an example of a patent front page with all the expected content.

Types of Patents

There are three types of patents, namely, design, utility, and plant patents. According to the United States Patent and Trademark Office, a design patent consists of the visual ornamental characteristics embodied in, or applied to, an article of manufacture. Therefore, the subject matter of a design patent application may relate to the configuration or shape, to the surface ornamentation applied to an article, or to the combination of configuration and surface ornamentation. A design patent protects only the appearance of the article and not structural or utilitarian features. A “utility patent,” on the other hand, protects the way an article is used and works. Both design and utility patents may be obtained on an article if invention resides both in its utility and ornamental appearance. A plant patent is purely related to the invention, discovery, and asexual reproduction of a distinct variety of plant.

Utility patents cover the most common categories of invention and are granted for inventions that produce a new and useful result (as opposed to design patents, which protect purely ornamental designs on useful objects). For an invention to qualify for utility patent protection, it must fall into one of the following categories of subject matter:

- Machines, which are generally composed of moving parts (such as a clock or an engine);

- Articles of manufacture, which are generally useful items with few or no moving parts (such as a screwdriver or bolt);

- Processes, which are stepwise methods (including software and methods of doing business); and,

- Compositions of matter, which include compounds and mixtures (such as man-made proteins and pharmaceuticals).

Parts of a Patent

A patent consists of several parts: a specification, usually one or more drawings, and one or more claims.

The specification is a major part of a patent, a written description of how to make and use the invention. The main parts of a utility application’s specification are:

- Title: A brief, technical description and identification of the field of the invention.

- Related applications: If a patentee application is related to a prior filing, like a provisional application, he/she must identify it by its serial number.

- Abstract: A 500-word brief description of how the invention works.

- Background: This consists of two parts. A description of the field of the invention and a description of the related art, which includes related patents and the problem that the invention solves.

- Summary: This is longer than the abstract and describes the problems solved by the invention and how it works.

- Brief Description of Drawings: This consists of a very short explanation of each drawing.

- Detailed Description: The is the core of the specification and describes the inventor’s preferred way and other ways of practicing the invention, along with a narrative that explains the drawings.

- Claims: This are the most valuable part of the patent. Claims are where the inventor stakes out the his/her invention. If a person or entity is making, using, selling, offering for sale or importing the claimed invention (as described by the claims of an issued patent), that person/entity is infringing the patent.

- Drawings: Drawings are not required for a patent filing, but the examiner may require the inventor to submit drawings if the nature of the invention is such that drawings would help the examiner understand the invention. Drawings must meet certain standards and requirements, such as margins, size and type of paper. Drawings further contain reference numbers. The inventor must identify all the relevant parts of his/her invention, identifying in the description what makes the invention novel. Each part gets a number in the drawings.

Patent Claims

The goal of the inventor should be to get claims that are as broad as possible while maintaining novelty compared to prior art. A claim consists of independent and dependent claims. For example:

Claim 1. A device for opening a can comprising, a formed body with an ergonomic handle; a tunable dial connected to a bladed wheel; and a lever to eject a cut can.

Claim 2. The device of claim 1 further comprising an ergonomic sphere removably attached to the tunable dial.

In the above example, Claim 1 is an independent claim because it references no other claims. Claim 2, on the other hand, is a dependent claim because it depends on Claim 1 (and references Claim 1). Obviously, independent claims are broader than dependent claims. Dependent claims are used to define and further specify the preferred or alternative ways of using the invention.

Independent vs Dependent Claims

There are two basic types of claims, namely the independent claims, which stand on their own, and the dependent claims, which depend on a single claim or on several claims and generally express embodiments as fallback positions. The expressions “in one embodiment”, “in a preferred embodiment”, “in a particular embodiment”, “in an advantageous embodiment” or the like often appear in the description of patent applications and are used to introduce an implementation or method of carrying out the invention.

An independent (“stand alone”) claim does not refer to an earlier claim, whereas a dependent claim does refer to an earlier claim, assumes all the limitations of that claim and then adds restrictions (e.g. “The handle of claim 2, wherein it is hinged.”) Each dependent claim is, by law, narrower than the independent claim upon which it depends. Although this results in coverage narrower than provided by the independent claim upon which the second claim depends, it is additional coverage, and there are many advantages to the patent applicant in submitting and obtaining a full suite of dependent claims:

An independent claim is typically written with very broad terms to avoid permitting competitors to circumvent the claim by altering some aspect of the basic design. But when a broad wording is used, it may raise a question as to the scope of the claim itself. If a dependent claim is specifically drawn to a narrower interpretation, then, at least in the U.S., the doctrine of differentiation states that the independent claim must be different from, and therefore broader than, the dependent claim. The doctrine dictates that it “is improper for courts to read into an independent claim a limitation explicitly set forth in another claim.” This means that if an independent claim recites, say, a chair with a plurality of legs, and a dependent claim depending from the independent claim recites a chair with 4 legs, the independent claim is not limited to what is recited in the dependent claim. The dependent claim protects chairs with 4 legs, and the independent claim protects chairs with 4 legs as well as chairs having 2, 3, 5 or more legs.

In practice, the independent claim broadly describes the invention while the dependent claim narrows the scope of the invention and more specifically describes the preferred embodiment(s).

Patent Claim Construction

In a patent or patent application, the claims define, in technical terms, the extent/scope of the protection conferred by a patent, or the protection sought in a patent application. In other words, the purpose of the claims is to define which subject-matter is protected by the patent (or sought to be protected by the patent application). This is termed as the “notice function” of a patent claim, to warn others of what they must not do if they are to avoid infringement liability.

The claims often use precise language. Certain words commonly used in claims have specific legal meanings determined by one or more court decisions. These meanings may be different from common usage. For instance, the word “comprises”, when used in the claims of a United States patent, means “consists at least of”. By contrast, the word “consists” means “consists only of”, which will lead to a very different scope of protection.

Furthermore, in U.S. patent practice at least, inventors may act as their own lexicographer in a patent application. That means that an inventor may give a common word or phrase a meaning that is very specific and different from the normal definition of said word or phrase. Thus, a claim must be interpreted by considering the definitions provided in the specification of a patent.

Interpreting what a patent claim means or how it should be construed (claim construction) plays a critical role in nearly every patent dispute case. Claim construction is central to evaluation of infringement and validity, and can affect or determine the outcome of other significant issues such as enforceability, enablement, and remedies.

For a patent to be granted, the claimed invention must be novel and non-obvious. To infringe on a patent one or more of the claims must be infringed upon. In the U.S., the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) during patent examination gives the claims the broadest reasonable interpretation (“BRI”) in light of the patent specification and drawings. The broadest reasonable interpretation of the claims must be consistent with the interpretation that those skilled in the art would reach.

However, district courts do not use the BRI standard when it comes to construing claim language. Instead, they rely on the Philips decision (Phillips v. AWH Corp.), under which claim terms are interpreted as to their ordinary and customary meaning as given by those of ordinary skill in the art at the time of the invention. The difference is that all intrinsic evidence (claims, specification and patent prosecution history) and extrinsic evidence (dictionary definitions and expert testimony) may be used to arrive at that interpretation. As such, absent a prosecution history estoppel (which can be used by a district court or the Federal Circuit to limit the scope of a claim), a patent can provide protection broader than the language of the claim as seen from the perspective of the patent specification.

The PDF below provides a good example of an approved patent.